Survivors

PARTNER IN HEALTH

Collins Shares His Experience with Prostate Cancer

PHOTO: DIANE BAKER

A medical school professor once told Dr. Francis Collins: if you’re going to get sick, at least try to be an interesting case. Collins inadvertently took that advice to heart earlier this year when he found himself not on the familiar physician-researcher side of NIH, but rather as a surgical patient.

Earlier this year, Collins was diagnosed with an aggressive form of prostate cancer. For five years, his doctor had been monitoring a modestly elevated PSA blood test associated with a rather unimpressive prostate MRI lesion, something common in men his age. Collins wasn’t worried. But then something changed, and the new diagnosis took him by surprise.

“I’m an outlier,” said Collins. “Most of the time when doctors do this kind of active surveillance with repeated testing, images and biopsies, men tend to stay in the same pattern for a long time. If you start out, as I did, as a Gleason-6 [on the prostate cancer grading scale], you often stay there for a decade or more. I broke the rules.”

NIH Protocol

PHOTO: CHIA-CHI CHARLIE CHANG

Five years ago, Collins’s doctor informed him of a slightly elevated PSA—the blood test for prostate-specific antigen. This health change inspired Collins to enroll in an NIH clinical protocol to monitor and test ways to improve screening and managing cancer.

“I was glad to serve as another data point they could add to this long-term study,” said Collins, who has dedicated his career to studying genetics and helping others—as former NIH director (2009-2021), former National Human Genome Research Institute director, current NHGRI distinguished investigator and, most recently, a patient partner in research.

Collins knew he had a higher risk of developing prostate cancer. His father had been diagnosed with the disease 40 years ago and suffered significant side effects from treatment.

When Collins saw his PSA go outside the normal range, he said, “I did my own due diligence, checking out what other institutions do in that circumstance, reading the literature. And, I concluded that our own doctors at the NIH Clinical Center were on the leading edge of research and clinical care. I concluded they were the people I could most count on to take care of me and make sure that whatever happened could add to the body of knowledge about this disease.”

“Our prostate MRI scan saw his tumor,” said Dr. Peter Pinto, senior investigator and urologic surgeon in the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Urologic Oncology Branch, who heads the clinical protocol. “We biopsied it multiple times over the years and it remained low grade. Then something changed in the biology of his cancer.”

For a PSA test, less than 5 is considered normal. In March, Dr. Collins’s PSA jumped to 22. A targeted biopsy showed the tumor had become a Gleason-9, on a scale that only goes to 10. The aggressive cancer was pushing through the outer layer of the prostate, but a very sophisticated PET scan with high sensitivity for prostate cancer cells found no sign of distant spread.

“The images showed my cancer had grown and spread itself around like a crescent and might have breached the capsule,” recounted Collins. “Then it was time to act.”

Surgery

On April 26, Collins underwent a radical prostatectomy, which removes the entire prostate gland and surrounding lymph nodes.

PHOTO: CLINICAL CENTER DEPARTMENT OF PERIOPERATIVE MEDICINE

“Today, this surgery is less invasive with better imaging and there’s less blood loss,” said Pinto, who was the lead surgeon. “You can go back to work sooner. You recover faster.”

Pinto performed a robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery. In the operating room, Pinto used the prostate MRI to guide the surgery “to improve [the chances of] removing all the cancer in the areas where it appeared to be breaking out,” he explained.

“When I remove the prostate, we go wide where we have to” with the goal of getting clean margins so no cancer is left behind. Using the MRI, he added, “enhances our ability to spare the muscles and nerves around the prostate to reduce the risk of side effects.”

Collins knew post-surgery incontinence was a possibility. “It’s a reality of what happens when you rearrange the plumbing down there,” he said. “That was my experience [initially], but it’s getting much better now.”

PHOTO: CHIA-CHI CHARLIE CHANG

A few days after surgery, Collins was re-admitted to the Clinical Center with a gastrointestinal complication that was swiftly addressed by his care team. A few days later, Collins had another unpleasant surprise: he got shingles, despite being fully vaccinated. “There’s a pretty big stress to the body with major surgery. I guess the immune system was distracted and the sleeping chickenpox virus took advantage,” Collins said.

The surgery was a success. “Using surveillance—PSA testing, MRI and biopsies—we caught the cancer before it became metastatic,” said Pinto. And, on July 31, Collins received a happy lab result, when his PSA was undetectable, less than 0.1. He’ll need to have this checked every three months for the next couple of years, but the signs now are really good.

Pinto said, “It’s great to see Dr. Collins benefit from all the work he supported as director here for so many years.”

Precision

Prostate cancer screening and surgical techniques have come a long way over the past decade, thanks to imaging technology pioneered by NIH.

For many years, Pinto was frustrated by testing methods that frequently led to overtreatment or missed aggressive cancer entirely, a standard of care that confounded doctors and left patients leery of getting tested in the first place.

“As a urologist, the idea of a PSA screening test leading to a prostate biopsy that was “blind” to the tumor location really disturbed me,” said Pinto. “I couldn’t think of any other solid cancer where a blood test led to a biopsy of the organ that was not directed to where the tumor was, instead just hoping to hit the cancer.” For decades, that was what doctors did. “I came to NIH to solve this problem.”

PHOTO: DANA TALESNIK

Pinto has worked at NIH for 21 years, collaborating with the same prostate imaging team—radiologists Dr. Peter Choyke, Dr. Ismail Baris Turkbey and Dr. Brad Wood, and pathologist Dr. Maria Merino—who together have changed the way prostate cancer is now detected.

Today, clinical guidelines advise a prostate MRI should accompany the PSA test if cancer is suspected. Now, if further testing is needed, there are new devices that offer a targeted biopsy. The biopsy device combines prostate MRI with ultrasound to direct the biopsy needles into suspicious cancer areas and can be performed in a doctor’s office.

“Over the past 20+ years, our NIH prostate team, working with medical industry partners, has taken this new biopsy device, UroNav, from concept to commercialization,” Pinto said. “We built it from the ground up and now MRI-directed fusion biopsies to diagnose prostate cancer is pretty much standard of care.”

PHOTO: NCI

With this imaging fusion technology, Collins commented, “You can be confident, when you do it this way, that the biopsies really are reflecting what’s going on and you haven’t missed the most important part of the prostate.”

Now, the NIH team has begun developing artificial intelligence analysis to better detect and confirm tumor characteristics. Pinto also is working on decreasing the harms of current treatments through his NIH clinical protocols that destroy just the tumor(s) within the prostate, an emerging field called focal therapy.

Someday, these advances will help determine which patients with prostate cancer will never need treatment and which may progress over time. Active surveillance is key. Pinto said, “If you could ensure the cancer is low grade and will not over time change, so you will die with it not from it, then we can just [watch it] and leave you alone.”

Care

Collins is grateful to have received his care at NIH.

“It was incredibly reassuring to see the remarkable compassion and excellent science and medical care that I received at the Clinical Center,” Collins said. “I can’t say enough about how impressive their team was with every detail.”

From the surgery, imaging and pathology team to the urology fellows to the nurses, “Everyone involved in my care was unfailingly polite, courteous, reassuring and supportive,” he added. “So I feel really good about this personal insight into the kind of care the NIH Clinical Center gives to people from all over the world who come here.”

Hope

Prostate cancer is still the second leading cause of cancer death for men and the most common non-skin cancer in men. But NIH-led advances in screening, detection and management are offering new hope.

“As we see these new technologies and advances from our clinical protocols become adopted more widely, we expect death rates will drop,” said Pinto, “and there will be less pain and suffering.”

Collins continues to candidly discuss his prostate cancer journey to impart lifesaving information. “I’m trying to be as transparent as possible,” he said. “I hope my experience will benefit others.”

Dr. Francis Collins

Francis Collins: Why I’m going public with my prostate cancer diagnosis

I served medical research. Now it’s serving me. And I don’t want to waste time.

Perspective by Francis S. Collins

April 12, 2024

Over my 40 years as a physician-scientist, I’ve had the privilege of advising many patients facing serious medical diagnoses. I’ve seen them go through the excruciating experience of waiting for the results of a critical blood test, biopsy or scan that could dramatically affect their future hopes and dreams.

But this time, I was the one lying in the PET scanner as it searched for possible evidence of spread of my aggressive prostate cancer. I spent those 30 minutes in quiet prayer. If that cancer had already spread to my lymph nodes, bones, lungs or brain, it could still be treated — but it would no longer be curable.

Why am I going public about this cancer that many men are uncomfortable talking about? Because I want to lift the veil and share lifesaving information, and I want all men to benefit from the medical research to which I’ve devoted my career and that is now guiding my care.

Five years before that fateful PET scan, my doctor had noted a slow rise in my PSA, the blood test for prostate-specific antigen. To contribute to knowledge and receive expert care, I enrolled in a clinical trial at the National Institutes of Health, the agency I led from 2009 through late 2021.

At first, there wasn’t much to worry about — targeted biopsies identified a slow-growing grade of prostate cancer that doesn’t require treatment and can be tracked via regular checkups, referred to as “active surveillance.” This initial diagnosis was not particularly surprising. Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men in the United States, and about 40

percent of men over age 65 — I’m 73 — have low-grade prostate cancer. Many of them never know it, and very few of them develop advanced disease.

But in my case, things took a turn about a month ago when my PSA rose sharply to 22 — normal at my age is less than 5. An MRI scan showed that the tumor had significantly enlarged and might have even breached the capsule that surrounds the prostate, posing a significant risk that the cancer cells might have spread to other parts of the body.

New biopsies taken from the mass showed transformation into a much more aggressive cancer. When I heard the diagnosis was now a 9 on a cancer- grading scale that goes only to 10, I knew that everything had changed.

Thus, that PET scan, which was ordered to determine if the cancer had spread beyond the prostate, carried high significance. Would a cure still be possible, or would it be time to get my affairs in order? A few hours later, when my doctors showed me the scan results, I felt a rush of profound relief and gratitude. There was no detectable evidence of cancer outside of the primary tumor.

Later this month, I will undergo a radical prostatectomy — a procedure that will remove my entire prostate gland. This will be part of the same NIH research protocol — I want as much information as possible to be learned from my case, to help others in the future.

While there are no guarantees, my doctors believe I have a high likelihood of being cured by the surgery.

My situation is far better than my father’s when he was diagnosed with prostate cancer four decades ago. He was about the same age that I am now, but it wasn’t possible back then to assess how advanced the cancer might be. He was treated with a hormonal therapy that might not have been necessary and had a significant negative impact on his quality of life.

Because of research supported by NIH, along with highly effective collaborations with the private sector, prostate cancer can now be treated with individualized precision and improved outcomes.

As in my case, high-resolution MRI scans can now be used to delineate the precise location of a tumor. When combined with real-time ultrasound, this allows pinpoint targeting of the prostate biopsies. My surgeon will be assisted by a sophisticated robot named for Leonardo da Vinci that employs a less invasive surgical approach than previous techniques, requiring just a few small incisions.

Advances in clinical treatments have been informed by large-scale, rigorously designed trials that have assessed the risks and benefits and were possible because of the willingness of cancer patients to enroll in such trials.

If my cancer recurs, the DNA analysis that has been carried out on my tumor will guide the precise choice of therapies. As a researcher who had the privilege of leading the Human Genome Project, it is truly gratifying to see how these advances in genomics have transformed the diagnosis and treatment of cancer.

I want all men to have the same opportunity that I did. Prostate cancer is still the No. 2 cancer killer among men. I want the goals of the Cancer Moonshot to be met — to end cancer as we know it. Early detection really matters, and when combined with active surveillance can identify the risky cancers like mine, and leave the rest alone. The five-year relative survival rate for prostate cancer is 97 percent, according to the American Cancer Society, but it’s only 34 percent if the cancer has spread to distant areas of the body.

But lack of information and confusion about the best approach to prostate cancer screening have impeded progress. Currently, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that all men age 55 to 69 discuss PSA screening with their primary-care physician, but it recommends against starting PSA screening after age 70.

Other groups, like the American Urological Association, suggest that screening should start earlier, especially for men with a family history — like me — and for African American men, who have a higher risk of prostate cancer. But these recommendations are not consistently being followed.

Our health-care system is afflicted with health inequities. For example, the image-guided biopsies are not available everywhere and to everyone. Finally, many men are fearful of the surgical approach to prostate cancer because of the risk of incontinence and impotence, but advances in surgical techniques have made those outcomes considerably less troublesome than in the past. Similarly, the alternative therapeutic approaches of radiation and hormonal therapy have seen significant advances.

A little over a year ago, while I was praying for a dying friend, I had the experience of receiving a clear and unmistakable message. This has almost never happened to me. It was just this: “Don’t waste your time, you may not have much left.” Gulp.

Having now received a diagnosis of aggressive prostate cancer and feeling grateful for all the ways I have benefited from research advances, I feel compelled to tell this story openly. I hope it helps someone. I don’t want to waste time.

Francis S. Collins served as director of the National Institutes of Health from 2009 to 2021 and as director of the National Human Genome Research Institute at NIH from 1993 to 2008.

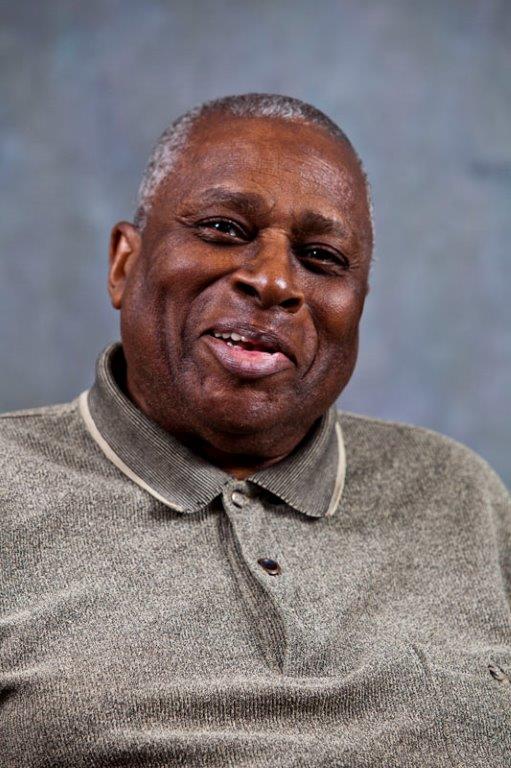

Mark Thompson

“For years, I avoided the PSA test because I heard it wasn’t very reliable. I am here today to tell every man to have this test – it saved my life.

I was diagnosed with Stage 4 prostate cancer. I am determined to fight against this because I still have a lot of life to live.

When I was first diagnosed in 2013, I called some friends and I also called (the late restaurateur) Matt Haley, who had been diagnosed as well. Amazingly, Matt returned my call. He gave me some great advice – “be where you are.”

That’s the thing about cancer. Each of us can only be where we are in the journey. We are truly a community of courage because we take care of each other. I’ve met so many people who are able to understand where I am. They give me courage, strength, and hope.

I am now working with advocacy groups to get the word out about the importance of having PSA tests and how therapeutic massage and bodywork has helped me.

It’s important to talk about cancer. It used to be something I barely thought about, much less talked about. Now, because of cancer, I am empowered to spread the word and help raise awareness.”

Norwood “Woody” Sloan

Survivor Turned Warrior Against Prostate Cancer

Updated from article: June 10, 2008

“I’m a more compassionate person because of prostate cancer. I was used to giving orders. Now I’m not interested in giving orders as much as listening.”

I spent 20 years in the Air Force and then worked for AT&T management for 20 years and never called in sick. “My health was excellent and I never missed a day of work.” So it came as a surprise to me, a Philadelphia native, right before my retirement from AT&T, I started experiencing problems. It was Christmas Eve, 1990 in Washington, DC. I was driving on the Beltway to attend a holiday office party and needed to pull over at every available rest stop. That’s when I realized I had a problem. My family doctor sent me to a urologist who ordered up a battery of tests, including a PSA blood test, bone scan and biopsy. At age 59 I was diagnosed with prostate cancer. As with many men who have prostate cancer, there were no warning signs. I never thought I would come down with cancer”.

Tough Decisions Ahead

The news of my diagnosis was difficult to take. I handled it the way most men handled it. I didn’t want anybody to know about it. I was very upset. At the encouragement of my physician, I joined a support group outside Washington, DC so I wouldn’t have to face the process alone. I learned about different types of treatment options from other men who had firsthand knowledge. Back in the ’90’s, most men would say, “I want the cancer out of my body”. I wanted to pursue surgery and have my prostate removed. The doctor decided to go in and take a look but did not remove the prostate. The cancer had already spread outside the prostate gland. He suggested an external beam radiation treatment and elected to undergo 39 days of radiation, followed by a combination of hormonal therapies. The hormone treatment resulted in unwanted side effects such as weight gain and breast enlargement. Worst of all, I had to deal with hot flashes the same as any middle-aged woman, Despite its discomforts, the treatment plan was successful and has been in the clear for 20 plus years. For the first 8 years I asked for the PSA to be checked every quarter and now I get it checked every six months. It’s good to listen to your doctor, but you must have a say in treatment. It’s nerve-wracking to this day. I always wonder if my PSA test is still non-detectable.

“Let’s Talk About It”

Early in his cancer experience,took an active role in helping men cope with the disease, and raising awareness of it. When his support group facilitator left a year after Woody joined, Woody was asked to become the facilitator. He accepted the position because he felt it should be a survivor, rather than a nurse, who led the group. I also became active in the battle against prostate cancer. For 7 years, I served on the Education Committee of the Capital Area Prostate Cancer Network (CAPCAN). I have served on the American Cancer Society Regional Prostate Health Awareness Committee for 11 years. I was interviewed for a film called “Prostate Cancer: Are You at Risk?” featuring 3 men undergoing different treatments for prostate cancer. The film was a turning point for me because I spoke frankly about my experience. That helped me cope. I stayed on as the facilitator for this support group for almost 10 years, until I left the Washington area. In 2001, me and my wife, May, decided to move to Middletown, Delaware, where we now reside. After the move, I joined the Warriors Against Prostate Cancer at the Christiana Care Health System in Newark, Del. He is a volunteer who helps to educate men about prostate cancer. Woody says that helping other people has had a profound effect on him. He leads “Let’s Talk About It,” a program with the American Cancer Society that starts dialogue in the African-American community about why early testing is important. Because African-American men have a higher risk for prostate cancer than men of other races, American Cancer Society guidelines recommend they begin yearly screening with a PSA blood test and digital rectal exam at age 45. The same goes for men with a close relative (father, brother, son) diagnosed before age 65. For men at average risk, the Society recommends that doctors offer the tests after discussing the benefits and limitations of screening and allowing them to make an informed decision about whether to be tested, starting at age 50. “That’s the one thing I find very rewarding,” he says. “When you go into a group of men and you relate your story and how you survived, then they are very willing to talk about it.”

‘You Have to Listen’

I emphasize the need for communication and education. My mother didn’t understand the danger of not telling her children my father had prostate cancer, After talking with relatives, we found out that his two brothers, two of my mother’s brothers, and several first cousins also had prostate cancer. After my diagnosis, I changed my lifestyle dramatically. I removed fat from my diet and followed the “3 B’s”: bake, boil and broil. I worked my exercise regimen, taking swimming and water aerobics classes. I continue to take water aerobics with other seniors 3 days a week. Stress was reduced in my life by moving to Delaware. Our house looks out on a golf course, I took golf lessons years ago but I do not play today. It is very peaceful.The green reduces my stress level. I really enjoy spending time with family and friends. Surviving prostate cancer has changed my attitude on life. Under a military career, you’re macho, You can withstand anything. If you hurt a little bit, shake it off. Well, all of that’s changed. I am no longer that macho person. I’m a more compassionate person because of prostate cancer. I was used to giving orders. Now I’m not so much interested in giving orders as listening. And that’s a big part of being able to convince people to do something about it. You have to listen.

Note: As of March 21, 2013, at the age 81 years, my cancer is still non-detectable.

Ben Fay

Prostate Cancer; A Personal Experience

In 1987 a gastroenterologist discovered a nodule on my prostate. At that time the PSA test was not in general use. I was 58 years old and my father had died of prostate cancer at age 71. A series of needle biopsies followed, the last of which was suspicious. An early version of the ultrasound guided biopsy revealed no cancer. About this time the PSA test became accepted and mine was followed every 6 months. The results hovered around 2 until 1996 when a 7.7 was returned. A six-month repeat showed a drop to 5.5. Another six-month result came back at 14.5.

The biopsy report showed a Gleason score of 9. Further tests showed that the cancer had left the capsule and gone to the seminal vesicles and the regional lymph nodes revealing a stage T3bN1MO cancer. Three second opinions later I chose the most aggressive treatment offered, an orchiectomy followed by 3D conformal external beam radiation ( IMRT was not yet in use) and a daily dose of Casodex. I tolerated the treatment well with only a couple of brief bouts of diarrhea and continued to bike about 50-75 miles per week. My PSA dropped soon to below 0.5 but after about a year it rose to 0.9 then to 1.5.

There was concern that the cancer was returning. Then the PSA began to decline, ultimately dropping to undetectable at 0.2 then at 0.1 where it has remained for about 13 years (over 16 years since diagnosis).

The physical side effects of the treatment have been nominal and manageable. Very minor urinary incontinence has appeared recently and has not been even a slight problem. Some radiation proctitus resulted in minor and very occasional rectal bleeding which was corrected by cauterization during a regularly scheduled colonoscopy. I still have occasional night sweats but these and the early-on hot flashes have diminished greatly over the years.

The initial emotional shock was traumatic given the high grade of the cancer. I despaired of seeing the Millennium but never stopped living each day to the fullest. I have come to enjoy a full and pleasant life and no longer think of prostate cancer as a sword over my head. Regular participation in 2 prostate cancer support groups has been a major factor in achieving my peace of mind.

I’ve come to realize that not all prostate cancer needs to be treated but when it does, for those like me at high risk, it is not a death sentence. It can be considered a chronic disease with the prospect of years of a good life, the quality of which can be enhanced by sharing one’s feelings and experiences with one’s peers.